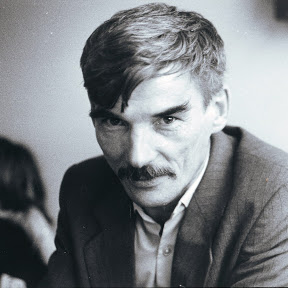

Yury Dmitriev in his own words

“For me it all began in the late 1980s. I’d heard that people had been ‘repressed’, but, somehow, we didn’t speak about it in our family. It turned out later that my mother’s father was dekulakised and sent to work on the White Sea Canal.

“My other grandfather was arrested in 1938 and died in the camps. He was an accountant on a collective farm and he caught it in the neck. Papa only confessed this to me in 1991 when we were coming back from the first funeral I organised for the victims of repression.

In 1988 I was an aide to USSR People’s Deputy Mikhail Zenko and the Besovets district was part of our territorial responsibility. A reporter I knew from the “Komsomol” newspaper, Sasha Trubin, rang me up: It looks as though they’ve found an execution site at the army base, he said. We need to get out there. I quickly contacted my chief, “We ought to go.” “Okay, get the car,” he replied. Off we went, taking Sasha with us. Guys from the prosecutor’s office, an investigator and district officials were already there … All in all, fifteen people, probably.

“There are bones here, so what? How can you tell they were shot?”

No one wanted to get involved. But I knew a little about osteology and from the position of the bones determined where the head should be. After a couple of minutes, I found a skull. I cleaned it and there, in the back of the head, was a round hole … “What are we going to do now?” It was a district-level conference with some outside experts.

“Let’s cover them up again. Who gives a damn!”

I said: “What do you mean, cover them up again? We should bury them: they’re human beings. We should give them a Christian burial.” (I decided to stress Christian values.)

“Who’s going to go to all that trouble?” There they stood, looking at one another. That’s your average man’s normal condition. He’s lazy. No one wanted to take on any extra work.

I looked at them and said: “Okay. If none of you can be bothered, let me deal with it. I’ll oversee and coordinate the work. Misha, what do you say?”

“Fine, I agree,” said Zenko. Well, if a USSR People’s Deputy said it must be done, that meant we’d do it. It was summer 1988. After it became clearer what needed to be done – the prosecutor’s office should carry out certain investigative procedures, remove the bones, record what had been found (how many bodies, and so on) – the investigator said: Since we’re dealing with these few poor fellows, there are no end of bones not far from here. They’re lying around, and no one takes any notice. Where are they? He told us. Come on, show us on our way back to town.

We took the investigator with us and drove to Sulazhgora, much closer to Petrozavodsk than Besovets. They were digging out sand for the silicate plant and at the bottom of the quarry, just as he said, there were piles of human bones: some complete, some damaged, and several skulls with holes in them.

“What’s going on here?” I asked.

“They keep tumbling out of somewhere. We wanted to bring our machines, investigate and dig them out, but it was impossible: the side of the quarry might collapse at any moment. We don’t know what to do with them.”

“Well,” I said, “couldn’t you give them a proper burial?”

“It’s not our responsibility.”

I spent several weekends there, gathering the bones, putting them into sacks and bringing them back to my garage. Then I got friendly with a tractor-driver who was working at the quarry.

“If you see anything,” I told him, “ring the prosecutor’s office”.

“I’ve already been told me not to ring the prosecutor or the police – they can’t do a thing.”

“Then ring me.” I gave him my number.

He rang. A great many more bones had appeared.

I went over there to collect them. Certain items also turned up – mugs, spectacles, underclothes. I kept on gathering the bones and items and then guys from the local Memorial society began to get involved. It was not so much tough as awkward to keep going on my own. A couple of times the earth buried me, and I could barely dig myself out.

On one occasion there were 20 deputies of the Petrozavodsk City soviet, an RSFSR People’s Deputy, seven or eight from Karelia’s Supreme Soviet, a platoon of border guards, eight from the MVD investigative centre and six or seven from the FSB archives. I had to put all that mob to work! I tied a safety rope to each of them: we didn’t want anyone going over the edge. Some were digging in one place, some in another.

Once one of the soldiers was set to work on the edge of the quarry. Bones were passed to him and he used a brush to remove the sand and muck. He sat there for some while. Suddenly he yelled and flipped backwards over the edge, dangling on the rope. We pulled him up. He had fallen nine feet, as far as the safety rope allowed.

“What’s up with you?!”

“He looked at me!”

“How could he look at you?”

I picked up the skull, dusted it off with the brush, and it stared back at me. A glass eye …

There were not one or two, but many graves on the site. All of them were small, twenty to thirty bodies in each. Regrettably, we could not excavate any one grave completely: we found them only after a landslip. Some of the remains slid somewhere else and it proved impossible to collect them all.

I often think that with our present brains and experience I could determine who was shot there. Then we were not experienced. The task we set ourselves was simple: collect the bones and give them a decent burial. Only later did I start wanting to know who these people were and why they’d been shot.

Excerpt from “My Path to Golgotha“,

an interview with Irina Galkova (Memorial)

Pingback: Thousands of victims of the Stalin regime – Worldviewer